Regional Director, EMRO WHO: Why elect another man?

8 May 2018

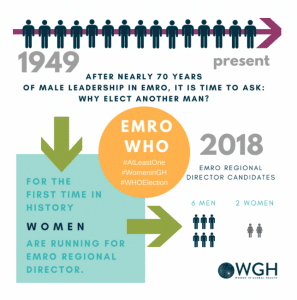

One of the items of business at the upcoming World Health Assembly in Geneva on May 19th, 2018 will be the election of a new Regional Director (RD) for WHO’s Eastern Mediterranean Regional Office (EMRO) following the untimely death in October 2017 of RD Dr Mahmoud Fikri.

In 2017 the election of Dr Tedros Adhanom promised a new approach and renewed focus on gender equality both in WHO’s leadership and programming based on the understanding that gender equality is smart global health. The achievement of gender parity in leadership at WHO headquarters has not yet been matched by similar progress at regional and country levels. WHO currently has four women Regional Directors out of six (EMRO is the sixth WHO Regional Office).

Since its establishment in 1949 EMRO has had five Regional Directors, all of them men. Appointing a female Regional Director in EMRO would show that this region of WHO is shifting its mindset. After nearly 70 years of male leadership in EMRO it is time to ask:

Why elect another man as Regional Director EMRO?

Gender Equality is Critical for Health in the EMRO Region

WHO EMRO serves the WHO Eastern Mediterranean Region, with 21 Member States and Palestine (West Bank and Gaza Strip), and a population of nearly 583 million people. The 21 countries of the EMRO region [1] are highly diverse ranging from some of the richest countries in the world (Qatar, Kuwait) to some of the poorest (Yemen, Sudan). Many countries in the region are currently affected by conflict (Syria), others are emerging from conflict (Afghanistan). Despite advances in the region since EMRO was established, many countries score low on indices of gender development and equality.

In 2015 only 4 countries in the EMRO region were ranked amongst the top 50 countries globally on the Gender Inequality Index [2] and none made it into the top 25 [3]. Seven EMRO countries had female labour force participation rates of 20% or less in 2015 [4] (those figures indicate women’s autonomy and access to income but do not record women’s substantial unpaid work). And the maternal mortality rate amongst EMRO countries ranged from 4 maternal deaths per 100,000 live births in Kuwait to 396 in Afghanistan in 2015. [5] There is therefore, strong reason for the EMRO region to prioritise both women’s health and gender equality as a key determinant of women’s health.

Currently at global level, women make up around 70% of the global health and social care workforce. In the EMRO region female doctors, nurses, midwives and community health workers play a vital role on the frontlines of health, delivering health and social care to millions, often in insecure and high-risk contexts, yet only 6 out of 21 (28%) Ministers of Health in 2018 were women and 8 out of 18 (44%) WHO Head of Country Offices Staff are women. [6]

In most regions of the world, female medical students now outnumber their male counterparts. And although not so everywhere in the EMRO region, it is a growing trend. Female medical postgraduates, for example, have outnumbered male in Kuwait since 1993 [7] and a recent study in Oman noted that 61.5% graduate resident doctors were female in 2015. [8] These figures partly reflect a culturally gendered trend in some EMRO countries for women to study at university in their home country while their brothers are sent overseas. The entry of large numbers of women into medicine also reflects a cultural taboo in some socially conservative societies against female patients consulting male health providers. Where this is the case, it is critical for women and men to work in equal numbers in health and social care to reach all sections of the population and therefore realise the Universal Health Coverage goal of leaving no-one behind.

The conclusions of the Oman study on the feminization of the medical profession are relevant for the countries of this region and beyond:

“The trend is expected to have important consequences on future planning, given that women doctors differ from men in how they participate in the workforce. It may also potentially contribute to a shortage in supply due to difference in preferences and consequently affect the skill-mix and productivity. The cultural, social context and dimensions need to be explored and feasible options to be provided for better planning.” [9]

It is critical that women’s contribution to the health and social care sector in EMRO be recognized, counted and enabled. Currently, as elsewhere in the world, women working in health are clustered into particular specialisms and sectors (often lower status and lower paid) and women are not represented equally in decision making jobs. Typically, the health sector is staffed by women and led by men and health systems are undermined by loss of talent and loss of diverse perspectives.

The Race for the Next EMRO Regional Director

The race for the next RD EMRO is reaching its final stages and women are already handicapped as female candidates are outnumbered four to one by male. This is the first time in history that women are running for the RD EMRO position. Eight candidates for the RD post have been proposed by Member States from EMRO [10], two women and six men.

This does not reflect the role played by women in the largely feminized health and social care profession.

And the process has not followed the more transparent precedent set by the race for the position of Director General WHO in 2017 where candidates set out their manifestos, were interrogated by civil society and Member States and where the candidate selected could later be held to account for the commitments they had made. In the race for the DG WHO those commitments included commitments on gender equality and women’s health since both are critical to delivery of global health goals.

Our Asks

In deciding which candidate to vote for as Regional Director EMRO at the World Health Assembly, Women in Global Health ask the following:

-

Member States recognise the role of women as drivers of change in health in EMRO.

-

Member States recognise that gender equality is smart global health everywhere but particularly in EMRO given the needs and cultural norms of many countries in the region which impact upon the health of women, men and children.

-

Member States recognise the importance of women leaders as role models for both men and women in health. The fundamental change needed to deliver quality health and social care to diverse EMRO countries and to reach Universal Health Coverage will not be achieved by business as usual. Diverse ideas and new models of leadership are needed.

-

Member States interrogate candidates specifically on their record on promoting gender equality, ask how they propose to achieve gender equality in health in EMRO, ask for specific commitments and hold the selected candidate to account.

-

Member States base your decision on the criteria agreed within EMRO for the RD selection, particularly technical, professional merit and integrity, rather than political considerations

-

Candidates for Regional Director EMRO: declare your commitment to gender equality and state what you will do to lead change to achieve gender equality within WHO EMRO and to support the countries of the EMRO region in this area.

-

Civil Society Organisations in EMRO: work in your countries and at regional level to stress to your governments the importance of electing a gender transformative leader as the next EMRO Regional Director.

In previous competitions for leadership posts in global health the question asked has often been ‘why give the job to a woman?’ But after nearly 70 years of male Regional Directors in WHO’s EMRO, the question should be ‘why another man?’

References

[1] Countries in EMRO Afghanistan; Bahrain; Djibouti; Egypt; Iran, Islamic Republic of; Iraq; Jordan; Kuwait; Lebanon; Libya; Morocco; Occupied Palestinian territory; Oman; Pakistan; Qatar; Saudi Arabia, Somalia, Sudan, Syrian Arab Republic, Tunisia, UAE, Yemen.

[2] UNDP Gender Inequality Index is a composite measure reflecting inequality in achievement between women and men in three dimensions: reproductive health, empowerment and the labour market.

[3] UNDP 2016 Human Development Report, Table 5

[4] UNDP 2016 Human Development Report, Table 5

[4] UNDP 2016 Human Development Report, Table 5

[6] Women in Global Health Data.

[7] Al-Jarallah, Khaled F., and Mohamed A. A. Moussa. 2003. Specialty choices of Kuwaiti medical graduates during the last three decades. Journal of Continuing Education in the Health Professions 23: 94–100. [PubMed]

[8] Nazar A. Mohamed1*, Nadia Noor Abdulhadi1 , Abdullah A. Al-Maniri2 , Nahida R. Al-Lawati1 and Ahmed M. Al-Qasmi1 2018 The trend of feminization of doctors’ workforce in Oman: is it a phenomenon that could rouse the health system? Human Resources for Health (2018) 16:19 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12960-018-0283-y

[9] Source Nazar A. Mohamed1*, Nadia Noor Abdulhadi1 , Abdullah A. Al-Maniri2 , Nahida R. Al-Lawati1 and Ahmed M. Al-Qasmi1 2018 The trend of feminization of doctors’ workforce in Oman: is it a phenomenon that could rouse the health system? Human Resources for Health (2018) 16:19 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12960-018-0283-y

*Based on publicly available data.

[10] Dr Ahmed Salim Saif Al Mandhari (proposed by Oman), Dr Hamad Abdullah Al-Manie (proposed by Saudi Arabia); Dr Mustafa Osman Ismail Elamin (proposed by Sudan); Dr Maha El Rabbat (proposed by Egypt); Dr Muftah M. Etwilb (proposed by Libya); Dr Rana A. Hajjeh (proposed by Lebanon); Dr Mohammed Jaber Hwail (proposed by Iraq); and Dr Mohamed Abdi Jama (proposed by: Somalia).