Women leaders: Judged by different standards?

2 May 2017

With the WHO Director General elections less than a week away — and elections being on everyone’s mind. Women in Global Health applies a gender lens to the election and asks what role gender bias may have played in assessing the three candidates? None of us is born biased for or against different genders, races, religions and beyond. Gender bias is linked to deep rooted gender norms, driven by history, culture, society and much more that shape us all. In this blog we cite a recent NYTimes piece and other releases, about the DG election to show that even serious journalists trained to report facts can slip into gender bias to the disadvantage of highly qualified women in global health. And this, in turn, is to the detriment of global health more widely.

We know women are underrepresented in all areas of leadership. Only 50 women in human history have ever headed a nation state – only 20% of the world’s parliamentarians are women, and a paltry 18% of ministers globally are women [1]. The numbers are slightly better with Ministers of Health averaging at 30% in 2017 [2]. Although change is moving slowly in the right direction, countries with the best records on female parliamentarians such as Rwanda with 63% (2016), drove change by recognising historic gender bias and taking measures to fix it.

It is readily recognized that the experiences of men and women running political campaigns are vastly different. Politics is framed as a masculine domain, which inhibits women from easily fitting into the space [3]. The media plays a particularly important role in reinforcing politics as a gendered domain where women do not fit and are not welcome. Gender discrimination by the media, often belittling female candidates and their records, is seen everywhere in the world, even in countries that are seen as more gender equal [4]. Research has shown that journalists regularly use language and imagery that emphasises that women do not fit into politics [5]. The most common way this is seen is through the use of sports or war metaphors to describe campaign events [6]. Additionally, while women often receive more media coverage, the stories tend towards the personal, and often minimize or omit their policy ideas and platforms [7].

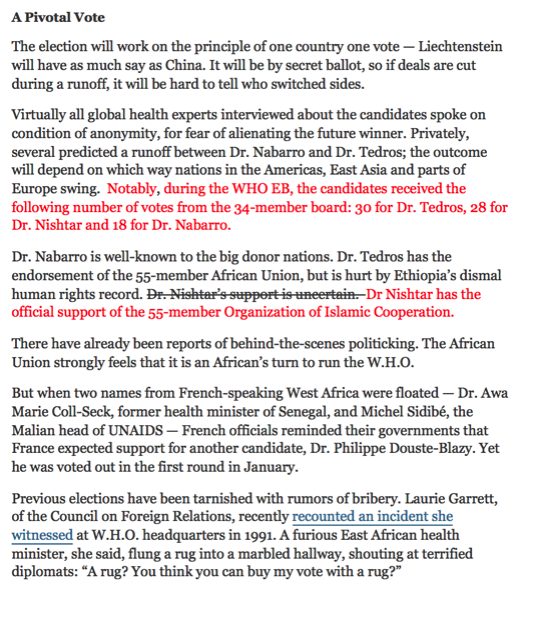

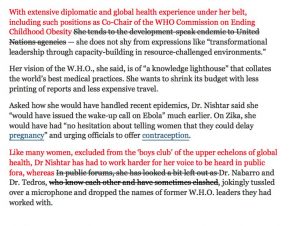

Last month’s NYTimes article The Campaign to Lead the World Health Organization and its treatment of Dr. Nishtar’s candidature are typical of the treatment of women running for political office. While the professional records of the two male candidates were described seriously, the write up of Dr. Nishtar focused on personal information and her family. She was labelled an outcast – not fitting into the jocular relationship between Dr. Tedros and Dr. Nabarro. Whilst Dr. Nabarro was described as war-horse, Dr Nishtar was cast as indecisive and unable to describe her own strengths. Clearly, such a description would not be an asset for any candidate running for a global leadership role but most of all, we would argue it does not accurately reflect the depth of her professional career. WGH is suggesting the following edits to the NYT article to show the impact of gender bias and also how, in a better world, the article might have been written.

The Campaign to Lead the World Health Organization

Global Health

By DONALD G. McNEIL Jr. APRIL 3, 2017

For centuries women were excluded from and discriminated against in the health professions. They were denied the opportunity to train as doctors and later denied the opportunity to reach leadership positions. Today they form the majority of the global health workforce but women still do not reach leadership positions in equal numbers to men. We can fix this. A critical first step is to recognise the gender bias that still operates in favour of men, address it and ensure gender equality at all levels of global health.

Disclaimer: We want to acknowledge the purpose of this article is not to endorse any particular candidate, but to highlight the serious issue of gender bias in global health, conscious and unconscious, because we can’t fix it until recognise it.